Income Distribution and Economic Freedom

The vicious ideological warfare between the Left and the Right is caused by one salient question: Just how useful is government in solving social and economic problems? A subsidiary issue is whether or not free-markets will inevitably cheat ordinary workers. Will companies always skew the wealth they create towards the richest, the fabled 1%? What is the relationship between income distribution and economic freedom?

The Bones of Contention on Income Distribution

“Yes!” scream the minions of the Left. The rich will always grow richer and the poor poorer under free-market capitalism. In order to keep malignant companies under control, government must always closely supervise and regulate them. Government must force corporations to pay good wages by the coercive power of law.

“Are you kidding?” hoot the followers of the Right. Government never solves problems without creating even bigger and more dangerous problems as side effects. Government would do better to harness free-market incentives to induce companies to behave. Better to reinforce the inducements of competition to force companies to pay their workers well.

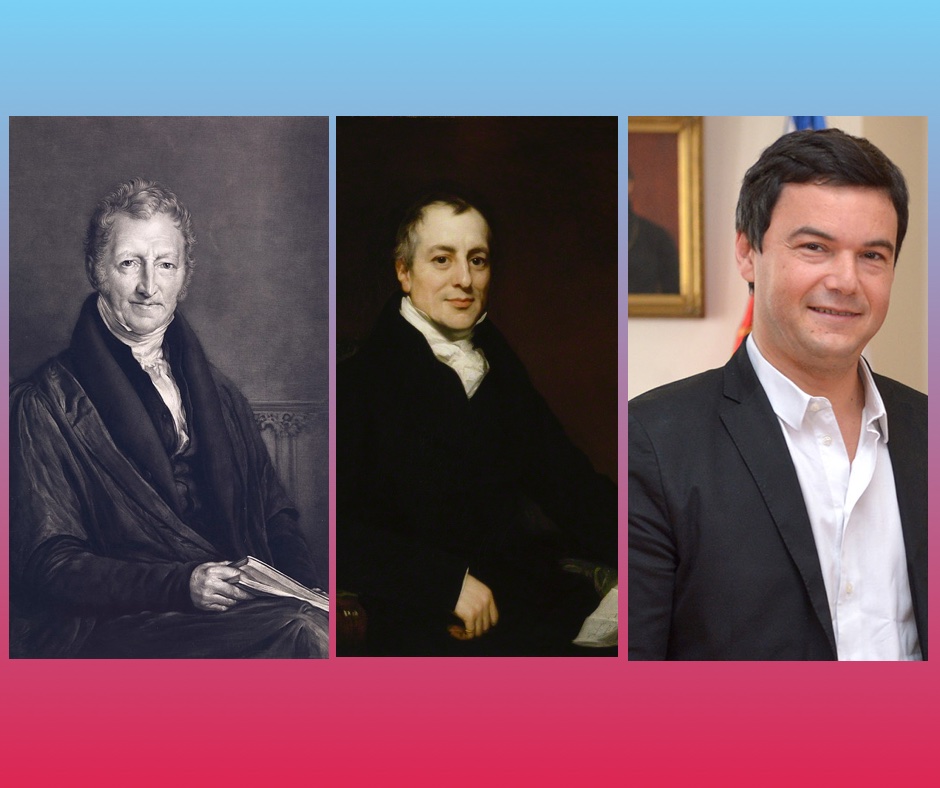

This argument over income distribution was kicked off by Thomas Malthus and David Ricardo in the early 19th century. Together they propounded what came to be called the Iron Law of Wages. What this faux law asserted was that economic incentives for the highest possible profits would lead companies to pay the smallest possible wages to sustain the lives of their workers. In modern times, the French socialist economist Thomas Piketty attempted to revive a version of the Iron Law. In his 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, he argued capital returns to stock, real estate, and other investors would outstrip wage gains for ordinary workers. As a result, he envisioned a growing income inequality between rich capital owners and the vast majority of people.

Piketty’s thesis has generated a very large amount of criticism. Although there are many ways to attack it, the most basic reason it is wrong is the same one that invalidated the original Iron Law of Wages. We know from history subsistence wages has not been the lot of most workers in economically developed nations. The reason it has not is skilled labor is itself a scarce economic commodity. If companies want to procure skilled labor, they must pay the market price for it in competition with their rivals. The law of supply and demand together with the law of marginal utility (known when acting together as Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand) will force employers to value labor at its proper worth.

If this criticism of the Iron Law based on neoclassical economics is correct, we should be able to find empirical data to validate it. If on the other hand the Left has the more correct view of social reality, that data should contradict the criticism and demonstrate growing economic inequality as economies become more capitalistic.

The Problems with Available Data on Income Distribution

Unfortunately, there is a not-so-small problem with the best data to settle the issue dispositively. The most natural variable to measure the equality of income distribution (or its lack) is called the Gini index. This index varies from zero to 100. If it has a value of zero, then the GDP is equally distributed throughout the population; if it is 100, then only one citizen possesses the entire GDP and everyone else has nothing. World Bank estimates of Gini indices for various countries in various years can be found here.

To settle the argument over whether or not free-market capitalism is better than some form of dirigisme, we need in addition a measure for how much a country’s government controls and manages its country’s economy. This is given to us by the Heritage Foundation, which every year calculates an Index of Economic Freedom for every country that has available data. It is also designed to vary from zero to 100. If zero, the country’s economy is completely under the control of its government; if it is 100, then freedom from government control is complete. You can find these indices for various countries in different years here. For the rest of this essay, I will refer to a country’s index of economic freedom as simply its “economic freedom.”

Our biggest problem is with the availability of the Gini indices for different countries in every year: They are not generally available. For some countries, for example many European countries, they are calculated every year. For some countries like the United States, they are calculated every three or four years. For some, they are seldom calculated and then erratically. For a few like North Korea, they are not available at all!

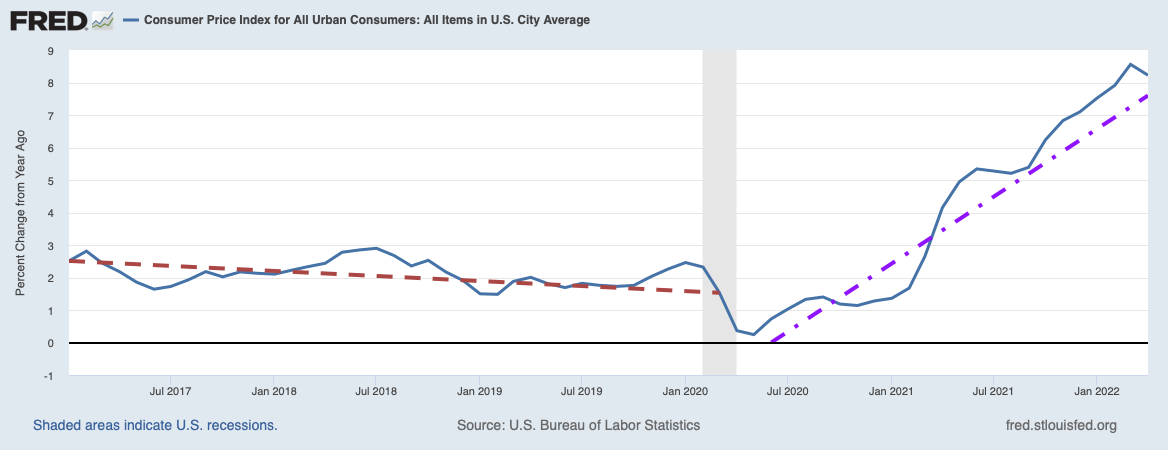

In the past, I have handled this problem by using the most recent calculation of a country’s Gini index to pair with its current economic freedom. The justification for this was most countries’ economic freedom varied slowly over a period of a decade or less. Following this procedure produced the following scatter plot of countries’ Gini indices versus their economic freedom in 2017.

Data Source: Heritage Foundation and the World Bank.

The brown line is the linear trend for the data, which obviously has a negative slope. The Gini index clearly tends to decrease as economic freedom increases. This means income distribution tends to become more equal as governments have less control over their economies. Note also that different colored points denote countries with different degrees of economic development. I somewhat arbitrarily declared countries to be developing if their GDP per capita was less than $15,000 in 2017 dollars, developed if their GDP per capita was greater than $35,000, and intermediate if they were anywhere in-between. The plot also strongly suggests — with some exceptions — that economic freedom is associated with greater economic development. This observation is largely confirmed by the following plot of nations’ per capita GDP versus their economic freedom.

Data Sources: Heritage Foundation and the World Bank

A Partial Solution

Nevertheless, a procedure where we use the most recent calculation for a country’s Gini index is troubling; there will always be some degree of error. In fact, we can follow a different approach that not only eliminates any such error, but greatly multiplies the number of available data points at the same time. Since what interests us is the values of Gini indices consistent with various values of economic freedom, we can take the data points from different years. The only constraint is that any one data point include data from a single year, albeit they can be different years for different countries.

In fact, we can use multiple data points for a single country. As a country’s economy evolves, its Gini index consistent with its current economic freedom will also change. We are constrained to use data points only from 1995 onwards, as 1995 was the first year the Heritage Foundation calculated the nations’ indices of economic freedom. This way of approaching the problem increases the number of data points from less than 200 to 1,126. Because the data points are taken from many different years, the dollars used to determine development status are in constant 2010 dollars. The numerical values at the boundaries have the same values as before. The resulting plot is shown below.

Data Sources: the Heritage Foundation and the World Bank

The heavy purple line is a linear trend produced by making a least-squares fit of a line to the data. It clearly has a negative slope. Note the greatest amount of data scatter is produced by the developing countries, with much less scatter among the intermediate and developed nations. Suppose we repeat the exercise using only the intermediate and developed nation data points. We then obtain the plot below.

Data Sources: the Heritage Foundation and the World Bank

The scatter has been much reduced, with the intermediate country points showing greater scatter than the developed countries. The negative slope of the linear trend is somewhat shallower. The trend’s slope using all countries was -0.1426, while that of the intermediate and developed countries was -0.1218. If we play this game one more time using only data from the developed countries, the scatter becomes less of course. However, the slope increases to a positive 0.2163.

Data Sources: the Heritage Foundation and the World Bank

The comparison of the last three plots leads to an interesting speculation, in which I will indulge in the last section.

Another question of great interest is the following: What happens to GDP growth rates as governments’ interference with the economy becomes progressively less? This question is answered in the following plot.

Data Sources: the Heritage Foundation and the World Bank

Among the undeveloped and some of the intermediate countries, we see GDP growth trending downward as economic freedom and economic development increase. As I noted in my last post, this is what we would expect from standard macroeconomic theory. However, as countries become developed, the average GDP growth reaches a minimum and the trend of GDP growth appears to become horizontal.

Conclusions and a Speculation

What should anyone, whether on the Left or the Right, conclude from all the data displayed above? I would propose the following list.

- Higher per capita GDP and economic development are almost synonymous with economic freedom. Less government control of the economy makes a country richer.

- Over the distribution of all countries on Earth, the Gini index trends downward with increased economic freedom and less government control. That is, increased economic freedom is associated with a more equal distribution of a country’s GDP among its people.

- As economic freedom and development status of a country increases, gains in making income distribution more equal lessen. For economic freedom sufficiently high, say above 70, the Gini index will trend higher, with income distribution becoming less equal.

- If we were to find different trends of the Gini index over different intervals of economic freedom, we would find the scatter of country points about the trend lines to become progressively less as economic freedom increases. This implies the Gini index becomes less determined by cultural and geographical factors, and becomes more tightly tied to the exclusion of government from control of the economy.

Point number 3 in the list practically demands an explanation. I would like to offer a speculation to explain it. I can not prove this speculation, but it is consistent with the data and seems eminently reasonable (at least to me!). As a country with low economic freedom and development lessens government control of the economy, it employs a larger fraction of its population with increased economic activity. The activity increases because stultifying government restrictions become less of a barrier to economic growth. Since most of company outlays almost always go to production costs, with a very small fraction paid out as dividends, those production costs including new investments will absorb most of the GDP growth. And almost always the largest production cost is the cost of labor. This fact, of course, is the major reason why the Iron Law of Wages and Thomas Piketty are wrong. As a result, increasing economic freedom among developing and intermediate nations will cause a larger fraction of GDP to go to the wages of the workers. The Gini index then decreases.

However, as a country becomes highly developed, capital needs for other than the payment of wages and production facilities rapidly rise. Simply applying more capital to pay for more labor or to invest in producing more existing goods is insufficient to generate economic growth. Instead, there are two reasons why capital must be redirected away from wage growth.

One is that as the total capital investment in an economy increases, the amount of annual replacement investments increases. Replacement investments are required to replace old worn out, obsolete, or broken production facilities and equipment, or to replace labor lost to retirement or lost for other reasons. If replacement investments are not made, the existing GDP can not be sustained and must fall. This means a larger fraction of capital investments must satisfy replacement investment needs.

Secondly, a mature economy can not generate more economic demand simply be producing more of the old goods and services in the old ways. Demand for these goods and services saturates. Without new demand there can be no new growth. As a result a mature, developed economy must do one of two things. Either it must invest to increase labor productivity (output per hour of labor expended), or to create brand new products and services consumers will demand. In the words of economists, the economy must increase its Total Factor Productivity. (See my three essays on the Solow-Swan economic development model, here, here, and here.) Either way, the fraction of capital investment that goes to increasing wages will decrease.

As a result the Gini index will increase (income distribution will become more unequal) for both reasons, as a smaller fraction of GDP is directed toward wages. This does not necessarily mean wages will cease to grow. The GDP might continue to rapidly grow with wages growing with it. It is just the fraction of GDP going toward wages that decreases, causing the Gini index to increase. If this is the case, ordinary people’s standard of living can continue to increase, even with an increasing Gini Index.

Given all this data, who would you vote for in the next election? Would you vote for dirigistes (progressives in the United States), who favor increased government control over the economy? Or would you vote for a neoliberal (Republicans in the United States), who favor minimal government control of the economy?

Views: 4,176

I cant believe this article has no coments!!!! Is sooo goood, thank you so much!!!