Romanticism and the Secular Religion of Progressive Democrats

The portrait above is of the famous eighteenth-century social contract philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. His romanticism seems to motivate much of the secular “woke” religion of present day progressive Democrats. Thinking about Rousseau’s romanticism might tell us how to start a religious reformation to convert the misguided “woke.” If you are among the “woke,” such contemplations will show you why the rest of us refuse to accept your religious beliefs.

The Romanticism of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Rousseau was one of three major social contract philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment. The other two were Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) and John Locke (1632-1704). What they held in common was the idea that the government (i.e. the sovereign) did not receive its authority directly from God as a grant. It received its authority from a social contract with the country’s citizens. Should the contract be violated or not fulfilled by the government, citizens would be entirely justified in replacing the sovereign with one that would honor the social contract.

Where the three philosophers differed were in the details of the social contract. Thomas Hobbes believed the only necessary requirement of the contract was that the sovereign must protect and defend the lives of the governed. Otherwise, the ruler could hold arbitrary power over the population. Hobbes asserted that without a sovereign, everyone would live in a state of nature in which there would be a “war of all against all.” In such an all-inclusive war, our lives would be “nasty, poor, solitary, brutish, and short.” For Hobbes, this unacceptable alternative justified a social contract with an otherwise totalitarian ruler. However, should the sovereign not protect the lives of law-abiding citizens, the population had every right to overthrow the sovereign and replace him with another.

John Locke agreed with Hobbes on the reasons for needing a social contract. However, Locke would put many more limits on the power of the sovereign. In contradistinction with Hobbes, Locke believed human nature is generally distinguished by reason and tolerance. He believed people could often govern their own lives. Accordingly, he believed every person had a right to defend his “life, health, liberty, or possessions.” In particular, he declared natural law required any social contract to protect not only the lives of citizens, but their property as well. The sovereign had a duty to protect these rights in the social contract. In addition, Locke believed in religious toleration for three separate reasons. First, human beings, especially those in government, can not reliably evaluate the truth-claims of competing religions. Second, even if earthly beings could make such judgements, enforcing a single “true religion” would not have the desired effect. All history screams at us belief cannot be compelled by violence. Consequently and thirdly, religious coercion would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.

All of these Lockean beliefs have led to his reputation as the father of classical liberalism. They are very much in conflict with the ideas of progressive Democrats, especially those who are “woke.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was much different from the first two social contract philosophers. This contrast was created by a very different view of a “state of nature” prior to more developed societies. Hobbes and Locke believed a “state of nature” implied a state of mutual competition unregulated by a central authority. Hence the “war of all against all.” Rousseau however thought there was no reason for a mutual competition, as there would be no conflict or property. Rousseau disagreed with Hobbes in Hobbes’ assertion that since man in a “state of nature… has no idea of goodness he must be naturally wicked; that he is vicious because he does not know virtue.” Instead, Rousseau claimed that “uncorrupted morals” prevail in the “state of nature.”

For Rousseau, a state of nature implied little or no society whatsoever. Because contact between individuals was rare, differences between them were of little significance. With few meetings between them, they would not have feelings of envy or distrust. The concept of property would be nonexistent, and certainly not something to be fought over.

Nevertheless, solitary existence as an animal in a state of nature was not the optimal human condition according to Rousseau. The optimal human development was that of what he called “savages.” By allowing some cooperation between people, it was better than the extreme of brute animals, but also better than the extreme of soul-destroying civilization with all its conflicts.

Rousseau claimed as savages grew less dependent on nature in a developing civilization, they became more dependent on each other. This development led to a loss of individual freedom. Having gone from a nomadic lifestyle to a stationary one in a village, the idea of private property was created. This was not an inevitable natural development. It was created by human choices.

For Rousseau, the “state of nature” is a normative, desirable condition. Compared to modern social organization, his ideal state of “savage” is barely above that of an animalistic “state of nature.” Any move back towards a state of nature from a civilized state would increase human equality and individual freedom. In particular, returning to a “state of nature” would disinvent the idea of property, the uneven accumulation of which has led to inequality and social domination of lower classes by the society’s elites.

Because of all these beliefs, Jean-Jacques Rousseau is often called the father of Romanticism. Romanticism is characterized by an idealization of nature, suspicion of science and industrialization, and an emphasis on emotion and individualism. It was a reaction against the social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment and the scientific rationalization of nature. It became a strong opponent to the Industrial Revolution. These Romantic ideas and attitudes strongly influence American progressive Democrats. They find an even stronger echo in the secular religion of the “woke.”

The Influence of Rousseau’s Romanticism on American Progressives

The influence of Rousseau’s Romanticism on the Democratic Party can be clearly seen in Democrats’ war on the U.S. Constitution. Our Constitution is itself one of the last and mature fruits of the Age of Enlightenment. Hostility toward the Constitution is then a hostility against the social norms of the Age of Enlightenment, one of the characteristics of Romanticism.

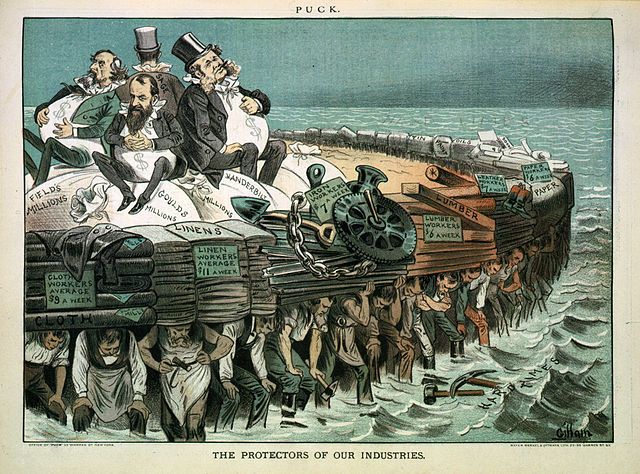

Yet another piece of evidence is provided by progressive Democrats’ war on free-market capitalism. I have written about this in the following essays:

- Crony Capitalism vs. Free-Market Capitalism

- The Democrats’ War on Economic Abundance

- How Progressive Democrats Try to Violate the Classical Laws of Economics

- The Inflation Reduction Act Is an Economic Disaster

Since private property is a necessary component of free-market capitalism, and private property is an affront for Romanticism, a hostility toward free-market capitalism is required by Romantic philosophy.

One final Romantic influence I will cite is the opposition of progressive Democrats to the burning of fossil fuels. This opposition is Romantic in at least two ways. First, a successful campaign against fossil fuels would push us back toward a more pre-industrial condition, closer to a “state of nature.” Second, progressive Democrats strongly believe that the burning of fossil fuels will greatly harm nature by increasing global temperatures through greenhouse gas warming. Since Romanticism exalts nature, a reduction in global warming by eliminating CO2 emissions would be considered profoundly Romantic.

The question of a neoliberal adherent to the ideas and ideals of the Age of Enlightenment must now be this: Are the assumptions made by Romantics true or false?

A Counter-Reformation Against Progressives?

The most direct attack on Romantic philosophy is on its most fundamental assumption. Romantics claim the “state of nature” is not a bad thing as asserted by Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, but a very good state that maximizes human freedom, human equality, and allows individuals the most authentic expression of their emotions. Also, Romantic philosophy can be attacked piecemeal by showing its various predictions of what is good and what is bad are false.

Romantic philosophy assumes that contacts between human beings in a “state of nature” are few and far between. Society hardly exists at all. With very few human contacts, conflicts over economic goods and from other causes are close to nonexistent.

This most fundamental of Romantic assumptions is close to unbelievable. The most basic human need in a primitive state is for food. Yet, in a “state of nature” the production of food is largely by hunting and gathering. According to the National Geographic Society, hunter-gather culture was the dominant way of life until sometime between 10000 BC and 9000 BC. This kind of culture is a subsistence lifestyle, which relies on hunting and fishing animals, and on gathering wild vegetation and other nutrients like honey. The National Geographic Society states “[u]ntil approximately 12,000 years ago, all humans practiced hunting-gathering.” The National Geographic reveals further the following:

Because hunter-gatherers did not rely on agriculture, they used mobility as a survival strategy. Indeed, the hunter-gatherer lifestyle required access to large areas of land, between seven and 500 square miles, to find the food they needed to survive. This made establishing long-term settlements impractical, and most hunter-gatherers were nomadic. Hunter-gatherer groups tended to range in size from an extended family to a larger band of no more than about 100 people.

Hunter-Gatherer Culture, National Geographic Society

Although hunter-gatherer groups were small, they were still more than large enough to ensure conflicts between members of a group. The assumptions of Hobbes and Locke about the nature of the “state of nature” seem far more likely than those of Rousseau’s Romanticism. No doubt group chiefs were chosen to regulate personal conflicts within their groups. At first, the social contract limiting a group chief’s power would be the minimalist one of Thomas Hobbes. However, as groups grew in size and technical ability in civilizations, one could easily speculate that additional restraints on the sovereign would be added to the social contract through political pressure, á la John Locke.

With this most basic Romantic assumption negated, societies no longer have to seek a return to less developed states. Closer to an undeveloped nature is not necessarily better. Indeed, an individual’s natural state in an economy is poverty, not prosperity. To prosper requires companies in free-market economies to apply division of labor, both between and within companies, to maximize production subject to demand for their products. To minimize waste and maximize their profits, companies need to maximize the mathematical product of their prices times the amount sold at those prices. This occurs at the intersection of the supply and demand curves in the law of supply and demand, as shown below.

Another way to rebut Romanticism’s aversion to free-market economies is to show how much better economies work for their populations when a government’s control over its economy is minimized. How can we either validate or rebut such a broad claim? First, we need a number of figures of merit that show how well a government’s policies are benefiting its citizens. Choices of these figures of merit include per capita GDP, GDP growth rate, the Ginni index, and the United Nations’ Human Development Index.

Second, we need an index that shows how much a government controls society, most particularly its economy. Control of the economy implies control over the rest of society. Examples of these indices are the Heritage Foundations Index of Economic Freedom (IEF), and the Cato/Fraser Institutes indices of Economic Freedom, Personal Freedom, and Human Freedom. I have demonstrated the equivalence of all these indices in the essay How Much Human Freedom Can We Find in the World?

Thirdly, we need a source for data on all the figures of merit for as many countries as possible. For this purpose, I have mostly used the World Bank and the United Nations.

The plots I display below were developed for the post Comparing the Economies of All Countries on Earth in 2021. They are scatter plots with one dot for each country on Earth for which there is data available. The x-coordinate for a dot is that nation’s Heritage House Index of Economic Freedom, which can vary from 0 to 100. If the index is 0, there is no economic freedom for individuals and the government totally controls the economy. If the index is 100, government has no control over the economy, and private individuals and companies have total control. The two extremes are polar opposite Platonic ideals, which might be approached but never reached. A dot’s y-coordinate in a plot is that country’s value for the figure of merit chosen for that plot. All plots are for the year 2021.

The source of all assets a country has to solve social and economic problems is its GDP. In particular, we need to know how much can be used for each person. Therefore, we need to see a scatter plot of each country’s per capita GDP versus their economic freedom.

The red curve in this plot is the best fit of an exponential to the scattered data. The fact there are more dots above the fitted curve with IEF greater than 60 demonstrates the growth of per capita GDP with increasing IEF is actually superexponential. This plot is unequivocal in showing that if you want a higher per capita GDP, you want to increase economic freedom and reduce the government’s control over the economy.

When the GDP growth rate is the figure of merit, we have a problem. It is well known that economic growth is generally much faster for undeveloped countries than for developed ones. The reason is developing countries have large quantities of unutilized labor and available capital (often from foreign investors). All they need for further development is to put that labor and capital to work. However, as they transition to developed status, most labor and capital have already been used. GDP growth slows. The only way a developed economy can increase growth is to do the harder job of discovering new ways of becoming more efficient, or developing new products.

Since growth rates are dependent on the level of economic development, we should make three separate scatter plots for three levels of development. If a country’s per capita GDP is less than $20,000 in 2021 U.S. dollars, we will classify it as a developing economy. If its per capita GDP is between $20,000 and $40,000, we will call it an intermediate economy. A per capita GDP of greater than $40,000 will denote a developed economy. By doing this we get the following three plots.

Data Sources: The World Bank and the Heritage Foundation

Data Sources: The World Bank and the Heritage Foundation

Data Sources: The World Bank and the Heritage Foundation

The red lines in these plots are linear best-fits to the data. They all have positive slopes, with developing and intermediate countries having the largest increases with increasing economic freedom. As advertised, developed countries increase their GDP growth rates the least with increasing economic freedom.

It is good to have a large per capita GDP. However, if a large GDP serves a country’s people well, it should be evenly distributed across the population as much as possible. How evenly it is spread is measured by the Gini Index. If the Gini Index were zero, then the GDP would be totaly evenly spread across the population. If it were 100, then only one person in the entire country would possess the entire GDP. The smaller a country’s Gini Index is, the more widely spread the GDP is. Below is a scatter plot of every country’s Gini Index versus its Index of Economic Freedom.

Data Sources: The World Bank and the Heritage Foundation

Clearly. as economic freedom increases and the government’s control over the economy diminishes, GDP tends to be more evenly distributed.

Next, the figure of merit to be considered is the U.N.’s Human Development Index. The HDI is a geometric average of a life expectancy component, an education component, and an income component. Each of these components varies from zero to one, with one being an optimal value. As a geometric average, the HDI will also vary from zero to one, with one being optimal. Zero would be catastrophic for a nation. What the HDI is designed to measure is the capability of a country to give each of its citizens a satisfying life. Below is the scatter plot for all the world’s countries of their HDI versus economic freedom.

Data Sources: The United Nations and the Heritage Foundation

The red curve is the best fit of a quadratic polynomial to the HDI. Not only does the HDI get better as the government is excluded from control, but the scatter of the countries’ points becomes less.

In all of these plots, the figures of merit get better as the government’s control over its economy gets less. In other words, as a country’s economy becomes more like a free-market capitalist economy, the better that country’s population is served.

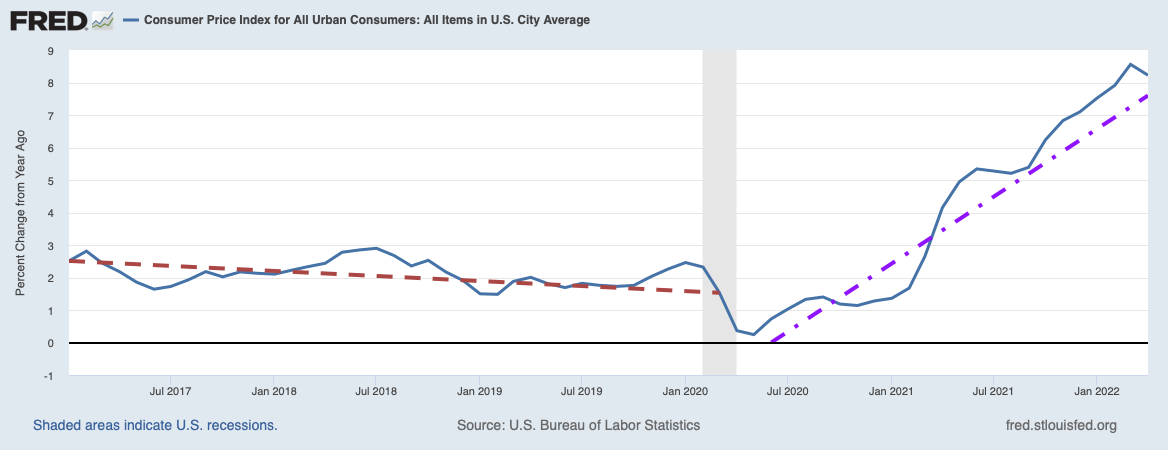

A final rebuttal is not so much about a failure of Romanticism, as a failure of Progressive Democrats’ use of Romanticism. The problem is the Democrats’ desire to eliminate the burning of fossil fuels. Progressive Democrats fervently believe that the emission into the atmosphere of CO2 is the primary cause of global warming. Moreover, they believe (or say they believe) that this warming will ultimately be catastrophic for life on Earth. Yet there are a series of four or five facts (depending on how you count them) about atmospheric carbon dioxide that show that atmospheric CO2 cannot possibly be the cause of the observed global warming. Moreover, Bjørn Lomborg has observed global warming is not an existential threat, even though it does pose a problem to which we need to adapt. All of this is discussed in the post The Idiocy of Joe Biden’s Climate Plan.

You might well object these arguments I offer are all rational and not necessarily effective against a religious faith. Nevertheless, if these arguments convincingly rebut the most fundamental of the faith’s assumptions, over time one might be able to chip away the followers of that faith. After all, the Protestant Reformation was able to reduce the power of the Medieval Roman Catholic Church. One can only hope.

Views: 1,876

Your insights are always thought-provoking.

Many thanks! Although my output has been considerably less lately, I still try to write posts backed up by empirical data.