Central Planning for Chaotic Social Systems

Chaotic Patterns Image Credit: Flickr.com/OLD SKOOL Santa Rosa

At the end of my last post concerning the problems of the Keynesian picture of secular stagnation, I commented on social systems being so complicated their description would best be accomplished by chaos theory (see also Chaos Theory for Beginners). In fact this is one of the very best arguments by conservatives against the social central planning to which progressives aspire.

Progressives’ Problems with Reality

It is not by any means the only argument! Many would claim preserving individual human freedoms from obliteration by the state to be at least as and probably more important. However, if one should grant the possibility of central government solution of social problems, the enthusiastic progressive could argue: “Just look at what we could accomplish in removing human suffering, if you would just be willing to give up some of your freedoms!” That can be a very potent argument, as socialists and communists have found through decades past. They promise a paradise on Earth for the very small and insignificant cost of your personal control of your own life.

However, historical experience causes us to question the very possibility of government control of our social problems. As we realize more and more how counterproductive government intervention in the economy can be, a little thought on why government finds control of the economy so difficult can be very rewarding. If you have not read many of my posts before, you might find reading posts in the Leftist Vs. Neoclassical Economics theme useful, particularly the posts The Keynesian-Neoclassical Conflict (2), Why Socialism Does Not Work, and The Complexity of Reality.

Having mentioned chaos theory, I should explain why I think it applicable to social systems such as our economy. The kind of system to which chaos theory can be applied is made up of a number, often in fact a very huge number, of interacting components that are not necessarily identical. By interacting with each other, the system’s components change their relationships with each other, mostly continuously but sometimes discontinuously with time. If these relationships are spatial and one were to take a snapshot, one might well see a pattern such as the fractal pattern shown in the image above. The prediction of the types of patterns that might result is one of the major applications of chaos theory, as well as whether the system might exhibit some kind of unstable behavior. See reference [S3].

The iconic example of a chaotic system is the world’s weather. Edward Lorenz, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology meteorologist, was renowned for his computer simulations of weather showing how unreproducible they could be because of the chaotic nature of the system. In 1972 he published an academic paper entitled “Predictability: Does the Flap of a Butterfly’s Wings in Brazil Set Off a Tornado in Texas?” This so-called “butterfly effect” captures how sensitive a chaotic system is to initial conditions at the start time of a system’s description or simulation. Infinitesimal differences in conditions at one time can lead to very large differences between two otherwise identical systems at a later time. Needless to say, such sensitivity makes it almost impossible to calculate a chaotic system’s later state from an earlier state.

The complexity of a system depends very much on how the system’s components interact. The weather is made up of the behavior of an immense number of different species of molecules, such as nitrogen, oxygen, water, carbon dioxide, etc. that interact with each other primarily through short-range collisions. They can interact with each other in some other ways, such as exchanging infrared photons (which is really just another kind of collision) as I described in the posts Basic Physical Processes of Greenhouse Gas Warming and An Infrared Photon’s Life in the Atmosphere. If this kind of system can be chaotic, how much more so can an economy be in which some of the interacting “molecules” are human beings! The behavior of a human being is innately far more complicated than that of any molecule, as any novelist or psychologist could tell you.

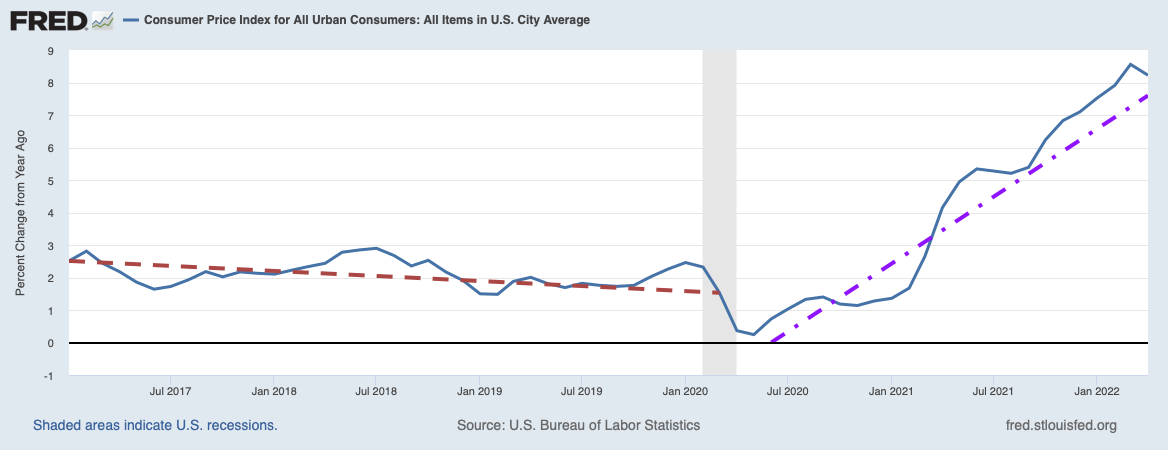

This enormous complexity of the average human being is what makes any system involving them as interacting components a chaotic system. One might be able to predict some typical patterns that might be formed, such as recessions and economic booms, but predicting exactly when or how or at what speed or size is definitely beyond our best computer programs. If physicists are very inaccurate in their prediction of global warming using computers, how much more can we trust Keynesians’ Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models?

No one should be surprised at government’s lack of capability at predictably stimulating the economy. As I wrote in The Keynesian-Neoclassical Ideological Conflict (2),

“Aha” exclaims the neoclassical economist, “this is exactly where the Keynesians get us into trouble! The government is a really lousy investor.” It is really hard to be a good investor at these national and international scales. It is hard enough to be a good investor at smaller scales, where you are only trying to find a few good companies for your IRA or 401K. To be a good investor, not just for yourself but for the entire economy, is practically impossible. To invest well for the entire economy means solving a nonlinear optimization problem for the optimal dollar inputs by the government. The quantity that we would want to optimize (i.e. maximize) would presumably be some aggregate like the GDP. If we could find some mathematical function to describe the GDP, it would be a function of hundreds of millions of variables for the U.S., billions of variables if we were to include the rest of the world to which our economy is connected. Why so many variables? Each individual in the world with dollars to spend would have several assigned to his behavior alone. Not all of these variables are independent but are connected to other variables by mostly unknown constraints. At the present time we cannot even pose the problem, let alone solve it.

Progressives’ Problems with the Electorate

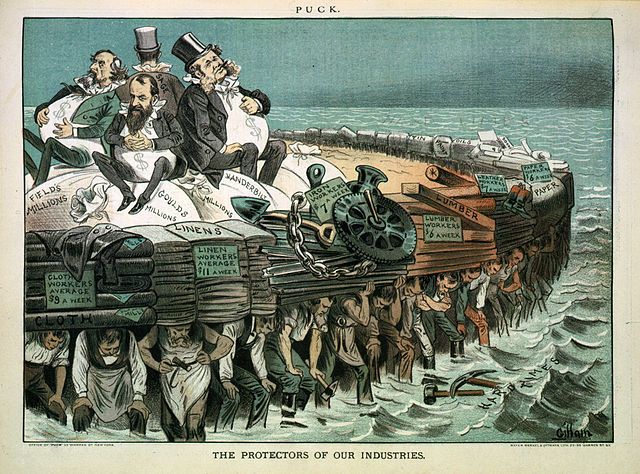

Given the problems anyone has in understanding social reality to the point where we could confidently improve our situation by government action, one should not be surprised at progressives’ incapability at delivering what they promise. Whether it is lack of victory in LBJ’s “war on poverty”, late 1970s’ stagflation while seeking stable economic growth, or the inflation of economic bubbles rather than promised growth, government failure over time is totally predictable.

So when progressives decide to institute some new government program, they have a credibility problem in getting people in general and Republicans in particular to go along with what they suggest. In recent years, especially with the advent of the Obama administration, the result has been deceptive statements in support of their policies that sometimes degenerate into downright prevarications. “If you like your doctor, you can keep your doctor. If you like your healthcare plan, you can keep your healthcare plan.” Some people have suggested this is merely evidence of the total incompetence of the Obama administration, but the verbal and videotaped testimony of Jonathan Gruber says otherwise. John O. McGinnis in a City Journal post, Why Progressives Mislead, comes to the following judgement.

But Obama’s fundamental problems stem less from incompetence than from his philosophy of governance. In his first presidential campaign, Obama took pains to distinguish his approach from the incrementalism of Bill Clinton and modeled himself instead on the transformational leadership of Franklin Roosevelt and of Ronald Reagan. During the race, and increasingly after the election, it became clear that Obama embraced a theory of dramatic political change—that of progressivism, which dates its American origins to an early-twentieth-century era of social and political reform. And he has adhered to it, despite some of the worst midterm election defeats faced by any two-term president.

McGinnis then notes the credibility problems progressives have and the increased resistance to their claims putting constraints on what they can enact. He then states,

Faced with these constraints, today’s progressives must resort to more misleading and sometimes coercive measures, as they seek to bring about equality through collective responsibility; they must rally support by looking beyond economics, to cultural and social identifications, in a bid to maintain the support of voters with little need for government intervention. They also want to limit the voices of citizens at election time, and thereby magnify the influence of the press and academia, which lean sharply in the progressive direction.

McGinnis concludes with a description of the passing of Obamacare as a particular example, and with comments on the increasingly autocratic nature of progressives and the Democratic party. As time goes on, government, particularly under the Democratic Party, can be trusted to solve problems less and less.

What We Must Yet Discover

I will continue to discuss how we can address social problems, particularly economic problems, in the very next post. Despite the fact these problems result from chaotic systems that can only be described approximately, there is still much a free people working in their own interests can do. One conclusion should be crystal clear: Central planning and control of these chaotic systems is a contradiction in terms.

Views: 2,204