The Progressives’ War On the Separation of Powers

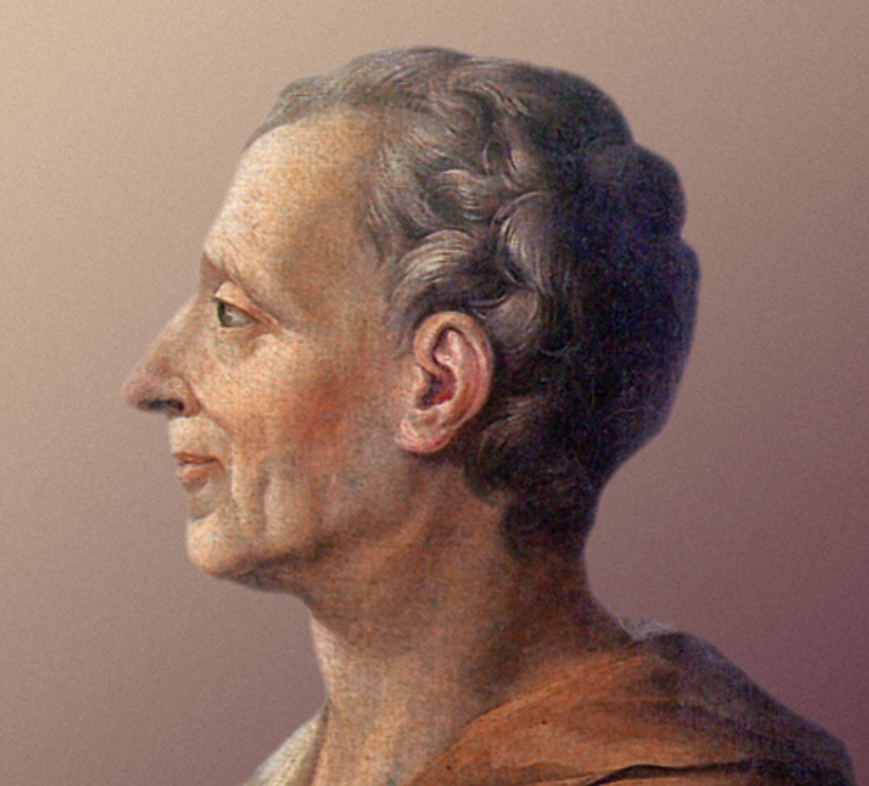

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu, 18 January 1689-10 February 1755

Wikimedia Commons / Currently at the Palace of Versailles

In my last two posts, I have tried to convince you of the threat to our liberties emanating from regulations imposed by the government’s executive branch. First in How a Democracy Evolves Into Fascism and then in The Dodd-Frank Act: A Giant Stride Along the Road To Serfdom, I pointed out how the power of the legislature has so often been delegated to the executive branch under the president. When the legislative power has leaked to supposedly independent agencies, such as the Federal Reserve Board of Governors or the Federal Communications Commission, the situation is often even worse, because those agencies usually have judicial powers as well, and can enforce their own edicts.

The Importance of the Separation of Powers

For reasons discussed in the next section, progressives have generally been at war with the U.S. Constitution’s separation of powers between the three major governmental branches: Legislative (the U.S. Congress), executive (the president’s administration), and judicial (the U.S. judiciary headed by the U.S. Supreme Court). If you hear progressives’ siren song urging centralization of power in the executive branch, you should consider why classical liberals, birthed by the Age of Enlightenment, thought separation of powers so vital for the security of citizens’ liberties.

One of those liberals was the 18th century French nobleman generally known from his titles as Montesquieu. He is the one accredited for first proposing the tripartite separation of government powers between a legislature, an executive, and a judiciary. In his classic book The Spirit of the Laws (De l’Esprit des Lois, 1748), Montesquieu wrote

When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may arise, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner.

Again, there is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control, for the judge would then be the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with all the violence of an oppressor.

Montesquieu’s work made a great impression on the authors of The Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. The Federalist Papers was a collection of 85 essays advocating the adoption of the U.S. Constitution

Wikimedia Commons / Publius (pseudonym)

published under the pseudonym Publius. Throughout these essays the separation of powers, as well as other “checks and balances” between the branches of government were advocated to ensure no one person or group of people had sufficient power to institute a tyranny. The founding fathers had had enough of that with King George III. In Federalist #47, James Madison explicitly cited Montesquieu and paraphrased him writing,

The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, selfappointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.

Any power can be misused and abused. If power is all centralized in one government organization, no matter how circumscribed the organization’s scope, its power will almost certainly be abused at some point. For example, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) may have the limited scope of regulating only interstate communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable. However, since it holds the legislative power of rule making, the executive power of enforcing its regulations, and judicial power in adjudicating individual cases (meaning they can levy fines), the potential for tyrannical application of the FCC’s power, even within its limited scope, is present. There are many who believe the FCC, under the urging of President Obama, has crossed that line in regulating the internet as a public utility. See reference [P5], Chapter 9. One is reminded of Lord Acton’s famous dictum: “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority; still more when you superadd the tendency of the certainty of corruption by authority.”

Progressives’ Impatience With the U.S. Constitution

Because of their faith in society’s rule by technocrats, progressives have always been enthusiastic in transferring legislative and judicial powers to executive departments and independent agencies. As I have noted elsewhere, the first big progressive divergence from classical liberalism began with the Woodrow Wilson administration (1913-1921).

Progressives have historically had a rather low opinion of the average American’s intellect and knowledge. Even some progressives are finding this mindset to be a problem, as can be seen in a Democratic Party oriented website post, Progressives: there are two profoundly condescending assumptions that will inevitably undermine all attempts to build an independent social movement that reaches ordinary Americans. Democracy Corps’ new methodology points the way to a superior approach on The Democratic Strategist website. In it, Andrew Levison writes,

The hard and inescapable reality, however, is that any progressive organizing effort will quickly find itself grinding to a halt if it does not honestly and immediately confront a critical problem – the existence of two profoundly condescending and deeply destructive assumptions about ordinary working Americans that are widespread in the progressive world.

The assumptions are these:

1. That progressives naturally understand the “real” issues that face ordinary Americans without having the need to do any serious “field” research to find out how ordinary people themselves define, understand and think about the issues.

2. That ordinary working Americans are basically gullible and can be easily manipulated by the messages they get from the media.

In combination, these two assumptions repeatedly sabotage all progressive attempts to build an independent social movement that gains the support of ordinary working Americans.

When you couple this low opinion with their inordinately high opinion of educated technocrats (quite often themselves), you can see how a proclivity for authoritarian government might develop. These kinds of considerations led Woodrow Wilson to believe the U.S. Constitution to be outdated and obsolete. The constitutional checks and balances were becoming a very serious obstacle against progressive policies that he felt unjustified. In a 1912 campaign speech Wilson expressed all this, saying the new generation of Americans must reject the old ways of the Founding Fathers to lead to a new, renewed America. To do this, he declared, required a very different view of the Constitution: one that evolved organically with the changing times. In that campaign speech, he revealed his fundamental vision that

Living political constitutions must be Darwinian in structure and in practice. Society is a living organism and must obey the laws of life, not of mechanics; it must develop. All the progressives ask or desire is permission—in an era when “development,” “evolution,” is the scientific word—to interpret the Constitution according to the Darwinian principle….

That is, the meaning of the Constitution was not constant, changing only with amendments according to the constitutionally mandated procedures; but malleable, changed by revised interpretations of judges that metamorphosed according to the requirements of changing times. What ties Wilson’s transmuted, “living” Constitution to the original? Not much, except perhaps a desire to fulfill the original purposes of the initial Constitution by interpreting it to meet those purposes in modern conditions. Yet, interpretations are notoriously volatile and ideologically subjective, changing from person to person. If the Constitution is not to be interpreted literally according to the words composing it, whose interpretation is acceptable? The apparent progressive answer seemed to be that any new interpretation mandated by a changed world must be generated by federal judges.

This is one vitally important reason — important to both progressives and neoliberals (synonymous with the misnomer “conservatives”) — to gain control of the presidency. Only with control of the executive branch comes control of who is nominated to the federal judiciary, particularly to the Supreme Court. Progressives need this power to ensure federal judges who are of their persuasion. Having their judges reinterpret the Constitution so that it meets their requirements of the day is their way of amending the Constitution. Having their judges and Supreme Court justices change the meaning of the Constitution according to their desires is considerably easier than going through the tortuous process amending it according to the Constitution’s specified procedures. Never mind that the reason it was made so difficult was to ensure the vast majority of the people acquiesced to the change! After all, the progressives reason, the mass of the common people do not really know what is good for them anyway!

And so it has gone, decade after decade ever since the Wilson administration. Progressives would gain occasional control of some federal judicial districts (the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals has been controlled by progressives for a very long time), coinciding with progressive control of the Supreme Court. When a U.S. appellate court would feed a decision to the Supreme Court with a changed interpretation under those conditions, the Supreme Court would then have the opportunity to “ratify” the amendment. The Supreme Court decisions Roe v. Wade and the decisions validating Obamacare were of this nature.

In the 2015 case concerning Obamacare (King v. Burwell), the main issue was whether or not health insurance subsidies could be paid if the insurance was bought from a health care exchange set up by the federal government rather than the states. The Congress had purposefully written Obamacare’s enabling legislation, the Affordable Care Act or ACA, so that only residents of states setting up their own state exchanges could get the subsidies. This was to force the states to bear the financial burden of setting up their state’s exchange, among other motives. The Court, using Chief Justice Roberts as a temporary progressive ally, found in favor of the government that the ACA was constitutional. Justice Scalia reacted by saying,

Words no longer have meaning if an Exchange that is not established by a State is “established by the State.” . . . We should start calling this law SCOTUSCare.

Scalia went on to declare,

Hubris is sometimes defined as o’erweening pride; and pride, we know, goeth before the fall. . . . With each decision of ours that takes from the People a question properly left to them—with each decision that is unabashedly based not on law, but on the “reasoned judgment” of a bare majority of this Court—we move one step closer to being reminded of our impotence.

The result of ignoring Congress’ clear intent was to allow the economic and human disaster of Obamacare to continue. Whenever tortured interpretations of legislative acts or the Constitution are allowed to override their plain meaning, it allows progressives to construct whatever government pleases them, no matter what the will of the people. After all, why should the progressives care what such dunces think?

Views: 3,299