U.S. Stock Markets and the Economy, February 2016.

Investors in the stock market getting their thrills!

Wikimedia Commons/Boris23

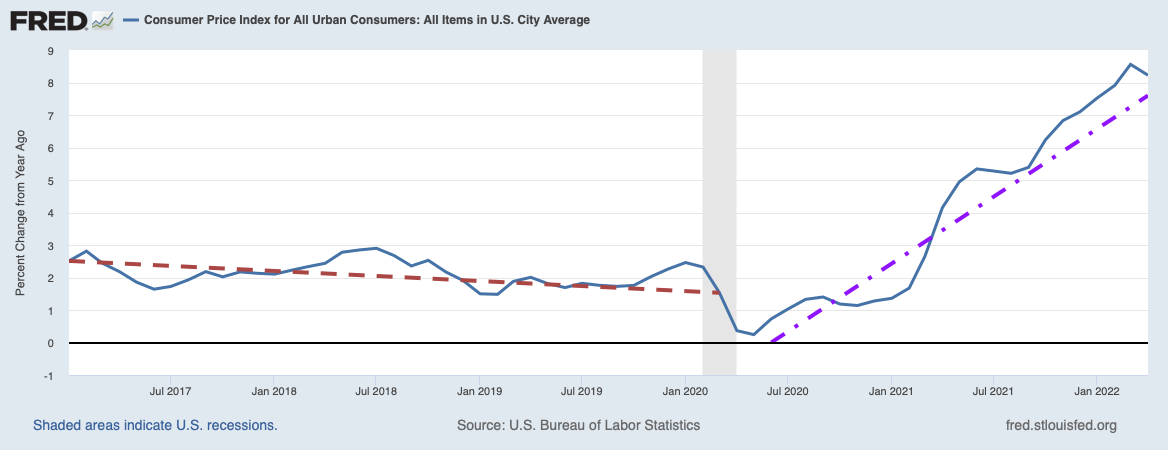

The last few weeks with the stock markets have certainly been an exciting roller coaster ride! As you can see in the chart below, market moves of more than 100 points in the Dow 30 index and 10 points in the S&P 500 – both up and down – have been the rule. Just as important as the size of the moves has been the volatility where a decline one day is followed many times by an increase the next. The daily variations in the indices are shown by the candlesticks; the superimposed blue curve is the 50 day moving average, while the red curve is the 200 day moving average. Clearly the trend of both indices is downward, but the market is fighting the decline every step of the way.

The Optimists’ Case and Its Rebuttal

Apparently, there still are a lot of people who do not agree that the world and U.S. economies are in a state of decay. One can still find optimists at financial companies such as Morgan Stanley, who say the recovery the U.S. currently is enjoying (as weak as it is) will probably continue until 2020! Optimists cite facts like continually improving employment numbers, an increase in consumer confidence, an improvement in household debt, and a corporate sector that has not overextended itself in debt. Let us look at these assertions point by point.

- Improving employment: In all of last year 2.65 million jobs were added by the economy and the U3 unemployment rate was reduced to 5.0%. Below is a graph of seasonally adjusted U3 unemployment from 1990 to the present.

U3 unemployment, seasonally adjusted from 1990 to the present. St. Louis Federal Reserve District Bank/FRED However, as many have pointed out, this unemployment rate of 5% is very deceptive. At the same time unemployment has come down, the precent of the adult population actually participating (working or looking for work) in the economy, the labor participation rate, has gone down to a 38 year low of 62.6%. This is illustrated in a graph of the labor participation rate below.

Labor participation rate from 1950 to present. St. Louis Federal Reserve District Bank/FRED While some of the decrease is due to increasing baby boomer retirements, a large part is because of increasing discouragement of even finding a job causing some people to withdraw from the labor market. The only reason the unemployment rate is as low as it is is because so many have left the labor market, making the number of unemployed still looking for a job a smaller fraction of a reduced work force. Labor and capital are the two most important factors of production; if the fraction of the population working goes down, so does the capacity to produce wealth. See the definition of a general production function and a Cobb-Douglas production function in the post The Solow-Swan Model and Where We Are Economically (1) for more discussion on this.

- Increase in consumer confidence: I have often thought the correlation between measures of consumer confidence and performance of the economy to be weak, and its citation being often a case of wishful thinking. In any case, the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment is falling. It came in at 92.0 in January, much lower than the preliminary estimate of 93.3 and below the 92.6 of December. When you add the fact December retail sales fell 0.1%, the changes in consumer confidence do not appear to be auspicious.

- Improvement in household debt: CNN Money reports household debt as a fraction of disposable income has come down from 135% in 2008 to 106% currently. While this is a big improvement, household debt is still enough to limit possible increases in expenditures. Meanwhile, the editors at the Bloomberg View have used other data from the Federal Reserve to demonstrate that the middle class carries a debt burden that is only slightly better from the depths of the 2007-2008 “great recession”. They report: “As of 2013, the average debt of middle-class families — those that fall within the middle three-fifths of the population by earnings — amounted to an estimated 122 percent of annual income, according to the Federal Reserve. That’s down a bit from before the 2008 crisis, but still nearly double the level of 1989.”

- Corporate sector not overextended: If one can indeed claim the corporate sector is not overextended in debt, it is because they do not think the business environment is healthy enough to invest in new productive capacity. However, in a financial milieu where the real interest rates were approximately zero, the corporations have indeed borrowed a lot of money to buy back their own stock. By reducing the total number of shares of their stock, they were able to increase the earnings per share and decrease their price to earnings (PE) ratio. This makes their stock more attractive to buy, but it does so at the cost of a debt burden. Reuters has reported, “Almost 60 percent of the 3,297 publicly traded non-financial U.S. companies Reuters examined have bought back their shares since 2010. In fiscal 2014, spending on buybacks and dividends surpassed the companies’ combined net income for the first time outside of a recessionary period, and continued to climb for the 613 companies that have already reported for fiscal 2015.” If interest rates should go up, many companies might find themselves in serious financial trouble. In any case, the assets they had on hand for investments have been greatly reduced by these buy-backs.

The Case for the Pessimists

If the economy’s picture given by the economic optimists is not nearly as attractive as they think, how strong is the pessimists’ case? I will begin with the 12 leading indicators I am following on my website. Of these, two are bullish (M2 monetary stock, building permits with a score +2), four are neutral (St. Louis Federal Reserve Leading Index, manufacturing jobs, durable goods orders, change of the national debt to GDP ratio for a score of 0), and six are bearish (M2 money velocity, average weekly manufacturing work hours, manufacturers’ new orders for non defense capital goods excluding aircraft, inventory to sales ratio, ISM purchasing managers index, copper prices for a score of -6). This yields an overall bearish score of -4. My leading indicators predict probable recession ahead.

To this direct picture of the U.S. economy, we must add how our trading partners in the international economy are doing. This presents us with an alarming picture. The OECD gives the value of U.S. imports in 2015 to be 17% of GDP and of U.S. exports to be 13% of GDP. The difference in the value of imports and exports, 4% of GDP, is the amount the U.S. owes to its trading partners. Every one percent of GDP it increases is a one percent reduction in GDP growth. With an average GDP growth since the end of the Great Recession of around 2.5%, turmoil in foreign trade has the potential to cause turmoil in the economy. if the rest of the world demands progressively fewer goods from us while we make larger demands on them, we could end up in recession in very short order.

This is exactly the situation that faces us with all of our trading partners simultaneously sliding toward or deeper into recession. China, having wasted approximately $6.8 trillion of scarce Chinese economic assets in bad investments, finds itself in a situation where it is getting very little return on their investment. They have a need for a great deal of new capital to support new projects to employ their suddenly idled workers. Much other past investment has gone into building ghost cities, not populated by hardly anyone. With internal needs for capital pressing, China’s demand for resources from the rest of the world must necessarily decrease. For example, with reduced economic activity, China has a reduced need for oil to fuel their vehicles. This is one of the explanations for the current global glut in oil, together with the new U.S. supply of oil from shale fracturing. Right now, the price of a barrel of oil is bouncing around $30 per barrel, reduced from over $100 per barrel about a year ago. These global oil price reductions are not good for the health of the U.S. petroleum industry, one of the very few bright spots in the U.S. economy. You can see in this how China’s economic troubles indirectly hurt the U.S. economy.

In addition to China’s problems, the world is also being afflicted with what is becoming a perennial and persistent problem: a stagnant Europe. Guntram Wolff, the director of the Bruegel think tank in Brussels, says analysts are projecting 1.5% growth of the EU’s economy. Europe will not be a growth engine to pull the world out of recession anytime soon. To be added to all this, the Japanese government is projecting Japanese real growth of only 1.7% this year, and the economies of Latin America are generally collapsing.

With all of these international economic problems, one could expect U.S. exports to fall, and this has been the case for some time as you can see in the plot below.

International problems might explain the decline in exports, but what can explain the fall in imports? With other countries suffering economic problems and the U.S. dollar increasing in strength, American importers should be able to get bargain-basement prices for needed imports. If imports are also falling, there must be a fall in demand due to declining economic activity in the U.S.

One effect of the slide toward global recession is the dumping of U.S. sovereign debt on the international market at the fastest rate in 15 years. This raises questions about who (other than the Federal Reserve) will be willing to help finance U.S. government deficit spending in the future, as I discussed in Will the U.S. Have Troubles Soon Financing Its Debt? .

Other signs of a U.S. slide toward recession can be seen in the slowing of M2 money velocity, and U.S. corporations abandoning the U.S. to relocate in other countries. Slowing money velocity means dollars are changing hands at a slower rate, which can only imply less economic activity. American companies fleeing the U.S. on the other hand illustrates how onerous government taxes have made U.S. corporations uncompetitive in the international markets. Finally, there is the very recent news that GDP growth in the last quarter was at the alarming low rate of 0.7%!

Sum all these factors together, and one would have to admit the economic pessimists have an excellent argument.

Back to “Bad Is Good”

What are the implications for American financial markets? There are more than a few professional investors who seem to have gone back to the mode where bad economic news is good news for the stock market. With the Federal Reserve now widely expected to refrain from raising interest rates for the rest of the year, any bad news for the economy might panic the Fed into going back to easy money policies. If bad news on the economy inspires the Fed to provide easy money that can be borrowed at an essentially zero interest rate, then professional investors can use this “free” money to buy more stock. Of course, they had better hope to sell that stock at a profit before markets respond to economic gravity and crash or before there are margin calls. What the pros have to hope for is another disconnect between the stock markets and economic reality.

What are the odds this disconnection will reoccur? There are several reasons why this is more than an idle hope. First, the Fed would not like to lose their cherished stock market-generated “wealth effect” that is supposed to open up the corporate purse strings for additional investment and economic demand by the wealthy. Second, if Keynesian monetary policy is proven mistaken and ineffective, the faith so many have in Keynesian economic thought will be called into question. This question of economic “face” should not be minimized. It would be very embarrassing for Keynesian economic scholars to admit an error in a perception of reality that has lasted for about 80 years. It is hard for anyone to admit having been wrong, but it is especially hard for scholars on the subject of their supposed competency.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, if interest rates – especially long-term interest rates – go up, the federal government might find the task of financing the national debt much harder, reducing the assets the government has to spend on everything else. These considerations caused me to speculate in an earlier post whether it was even possible for the Fed to raise interest rates. It is quite possible that with few other than the Fed being willing to buy long-term Treasuries and with interest rates going up, the Fed might be forced to buy the long-term Treasuries nobody else wants. Otherwise, the interest the federal government would have to pay to sustain the national debt might absorb an unacceptable amount of the government’s revenues, leaving too little for all of the government’s other operations. This difficulty is made more acute by the dumping of U.S. government Treasuries on the open market by foreigners. This increases the supply of Treasuries on the open market, which decreases their price. If the price goes down, their yield goes up, increasing the interest the government would have to pay to sell their next offering of Treasury bonds. The Fed not picking up the federal government’s tab might have disastrous consequences.

Because of all these considerations, stock market investors have every reason to believe the Fed will also continue to provide “free” money for them through the banking system. In fact I would not be very surprised if the Federal Reserve followed both the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank by applying negative interest rates on excess reserves and starting up QE4, the fourth U.S. incarnation of quantitative easing. Note that if the Fed initiates negative interest rates, the member commercial banks would have to pay the Fed for the privilege of depositing excess reserves. Almost certainly this would mean most if not all of the 80% of QE money that has been recaptured in excess reserves would be pulled out and injected into the economy. Then we may see some real inflation! Not to mention all the asset bubbles that would be inflated even further!

Views: 2,948