Dirigisme No Longer Works. What Replaces It?

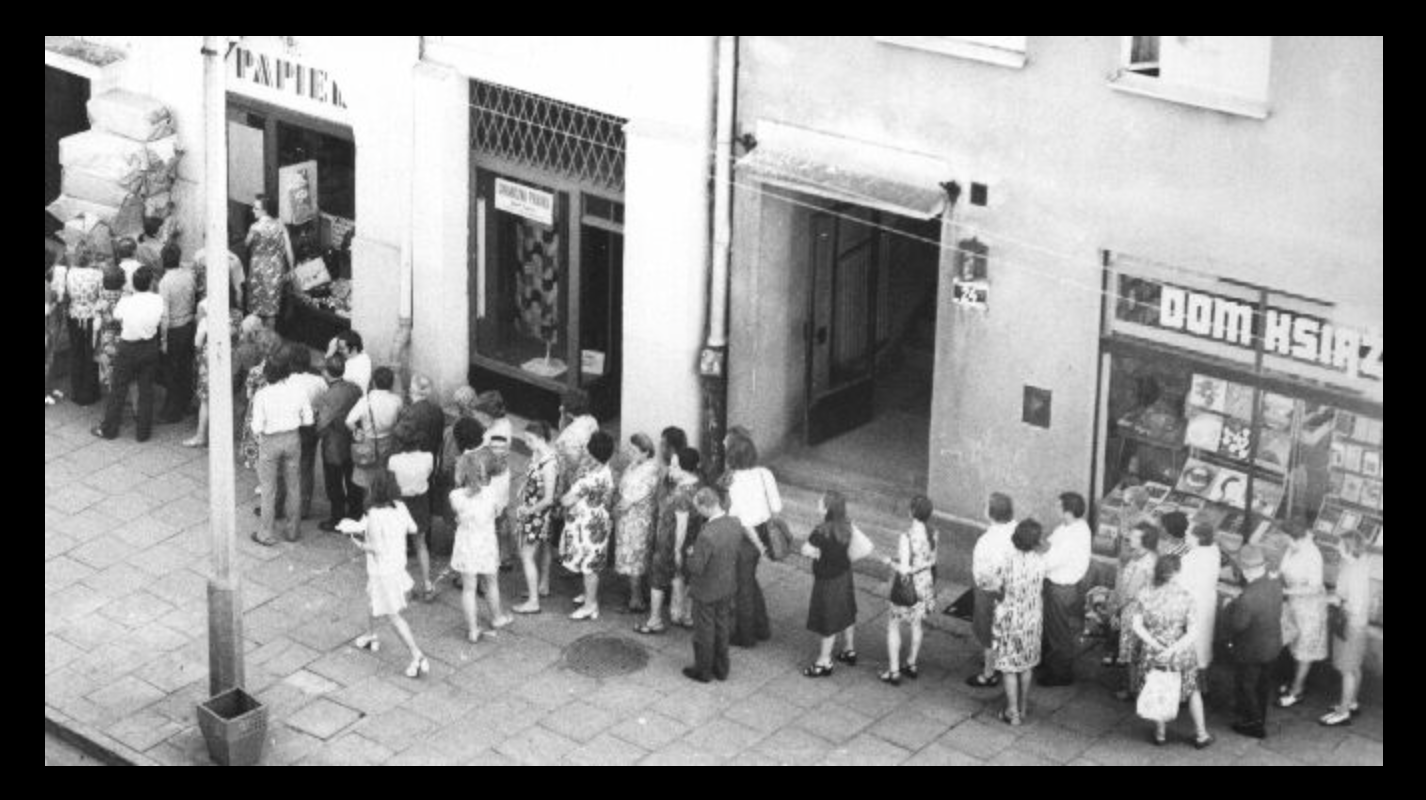

Line of shoppers in front of a Polish shop in the 1980s. A common sight in Warsaw pact countries ruled by communism.

Wikimedia Commons

Actually, dirigisme as a way of ruling a country has never really worked. Dirigisme, the philosophy that a country’s elites should rule a country though technocratic expertise, was just never applied with sufficient force to screw up the works. Not at least in Western countries until relatively recently. The Soviet Union was the first really huge example of how badly state control of the economy wrecked its functioning.

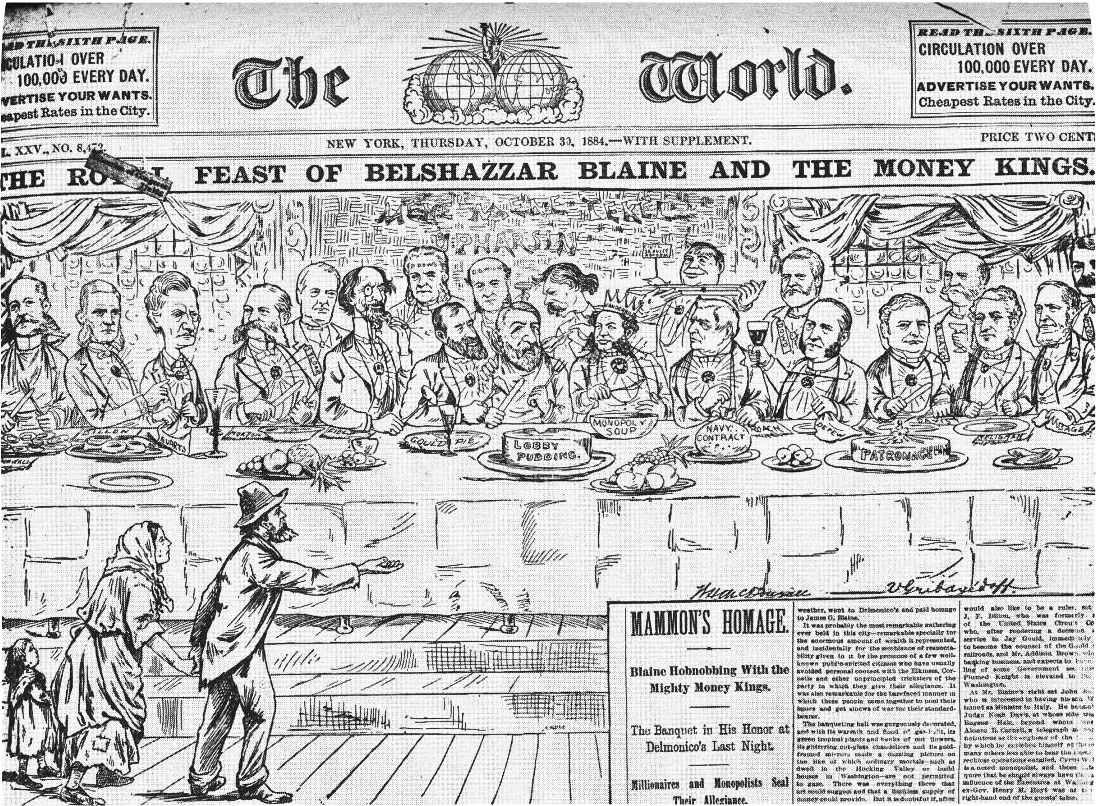

Becoming Aware of the Destructive Nature of Dirigisme

For a very long time — at least since the Great Depression in the 1930s — Americans have persuaded themselves that government interventions in the economy could actually solve economic problems they believed inherent to capitalism. At the time of the depression’s onset, a common view of its cause was

Wikimedia Commons

“cut-throat competition” between companies believed to be built-in to free-markets. This view motivated President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration to institute the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to mitigate this ferocious capitalist competition by bringing together industry, labor, and government. They were then expected to set codes for “fair practices”, as well as to set prices. There seemed to be no appreciation for how the disabling of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand could actually prolong the depression.

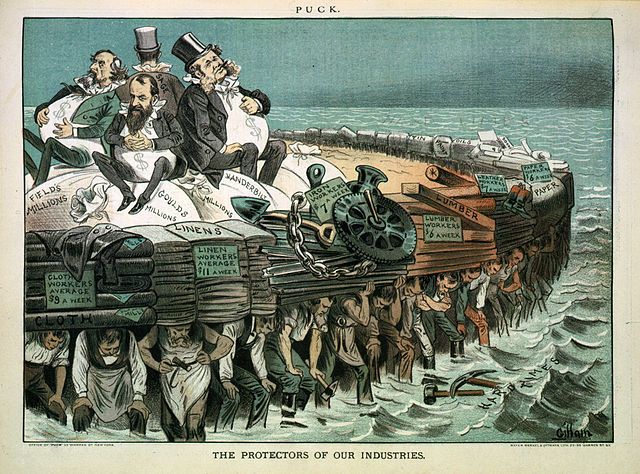

Dirigisme’s siren song was especially sweet to academic and political elites. It sang about the special power and status (not to mention the increased riches that would accompany them!) they would enjoy as the only ones with the requisite knowledge and understanding to rule society. From their point of view, the masses of common people had neither the education nor the wisdom to rule themselves. This is a fundamental attitude that almost defines progressivism, which depends on technocratic elites to ensure the general welfare.

Progressives’ view of reality during the Great Depression soon caused them to seize a second explanation to add to the first. The economist John Maynard Keynes taught his academic peers that free-market institutions together with fear of the economic future were motivating many people to save too much money, depressing demand for the economy’s output. His solution to this problem was to substitute government demand for the lost market demand, requiring government to direct and allocate capital flows. How could any politician with a thirst for power not respond positively to such a siren song?

It took a very long time after the Great Depression for neoclassical doubts to begin a substantive challenge to the Keynesian and dirigiste consensus. In 1963 the economist Milton Friedman and his colleague Anna Schwartz published an extremely seminal work that offered yet another explanation for the Great Depression that would eventually displace previous explanations as the primary cause. Entitled A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960, the book placed primary blame not on the free-market, but on the failures of an agency of the federal government, the Federal Reserve.

Beginning in 1928 the Federal Reserve switched from a quantity of money theory of price stability to a real bills doctrine (see here and here) that required material goods to back all money creation. Concerning the real bills doctrine, Friedman and Schwartz wrote

The foregoing fallacy survives today in the notion that the Federal Reserve should use easy monetary policy to lower interest rates to target levels consistent with full employment. For just as the real bills doctrine calls for expanding the money stock with rises in the needs of trade, so does the interest targeting proposal call for increasing the money supply when the market rate of interest rises above its target level-this monetary expansion continuing until the rate disparity is eliminated.

The problem with the real bills doctrine as Friedman and Schwartz see it is that under it there are no limits to the quantity of money. Whatever amount of money a banker is willing to lend to produce new goods is justified under the doctrine. Also, the doctrine can be construed to mean that as the overall demand for goods falls, then so should the money supply. This is exactly what happened after 1928. According to Friedman and Schwartz, the money supply dropped by about one-third between 1929 and 1933. The lack of liquidity caused many businesses to default on their debts, making them and the banks to whom they owed the debt bankrupt, thereby causing the banking system to collapse in 1932.

Another sign that something was going very, very wrong with neo-Keynesian thought, the brand of Keynesianism current at the time, was the stagflation of the 1970s, a simultaneous occurrence of economic stagnation with general price inflation. Neo-Keynesians declared that stagflation could not possibly happen because of what their Phillips Curve predicted. In their view economic growth strong enough to cause price inflation would inevitably lower unemployment.

The Phillips curve then showed an inverse relationship between inflation and the unemployment rate: when one rose, the other fell. The famed monetarist Milton Friedman and independently Edmund Phelps together explained stagflation in terms of monetarist ideas about inflationary expectations. The neo-Keynesians soon incorporated their criticisms into their own theories, along with responses to other New Classical criticisms, and in the process became the New Keynesians.

However the contradictions between the predictions of New Keynesians and actual reality began to accumulate as governments’ share of the GDP inexorably increased. Back in 1960 the expenditures of American governments at all levels — local, state, and federal — absorbed 26.5% of GDP, rose to a plateau of around 34% during the administrations of Reagan and Bush the Elder, then peaked at 35.4% during Clinton’s administration in 1992. Total expenditures then fell under the influence of welfare reform and cutbacks in defense spending to 30% in 2000. Following that, total government spending grew to around 32.5% of GDP during the regime of Bush the Younger. As a Keynesian response to the Great Recession during the Obama administration, the expenditures reached a peak of 39.3% in 2009-2010. Since then expenditures have fallen due to fiscal sequestration and Republican resistance back to 33.7%.

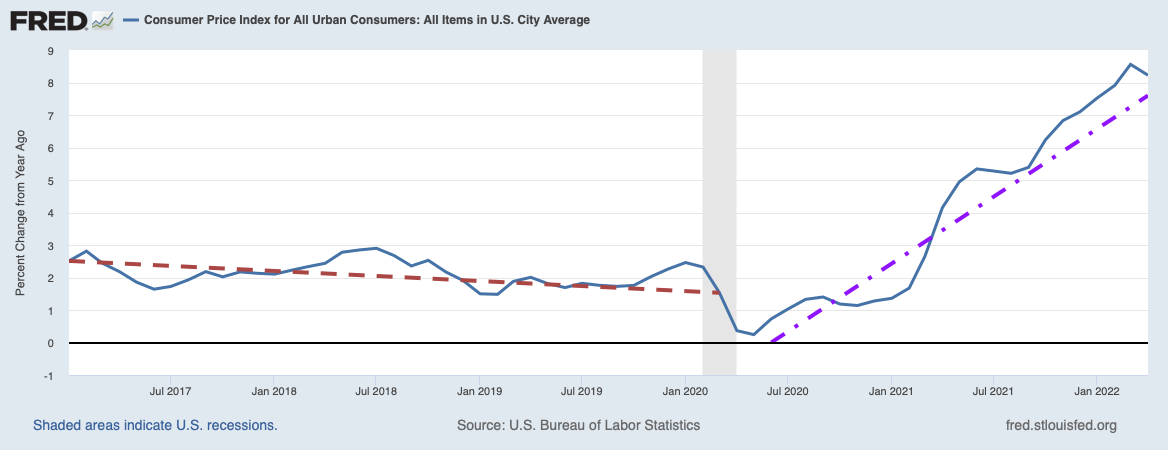

St. Louis Federal Reserve District Bank / FRED

Despite these heroic Keynesian efforts to stimulate the economy from 2009 to the present, they achieved very little as can be seen in the graph below.

St. Louis Federal Reserve District Bank / FRED

Throughout the Obama era, the real GDP growth has fluctuated around a two percent growth rate; over the past four quarters (Q4 2015 through Q3 2016), it has averaged 1.57%. The economy did technically recover from recession, but our growth rate right now is approximately half of what is considered to be our long term average. From 1948 to 2007, U.S. GDP growth averaged 3.41% per year. On the other hand, if you were to calculate a 10-year moving average of GDP growth, as the Gallup organization recently did, you would average over the short-term of recessions and booms to isolate the truly long-term trends. In performing this calculation from 1966 to 2016, Gallup found the really long-term trend of economic growth to be decreasing approximately 0.4% per decade.

The Gallup Organization

Gallup attributed this very long-term decline primarily to the destructive effects of the dirigiste state’s economic regulations.

In Europe and Japan, the results of Keynesian stimulus programs, both monetary and fiscal, have been similarly dismal. The annualized EU growth in the third quarter of 2016 over the the same quarter in 2015 was 1.9% and has been the same for the past three quarters. The similar statistic for Japan was 0.3% for the third quarter of 2016 and has been declining for the past three quarters.

These extremely bad results of the dirigiste state throughout the West and Japan have not totally escaped the notice of at least some of the academic economic elite, mostly Keynesian economists. Inspired by Larry Summers, they are attempting to explain our current economic stagnation in terms of a very old Keynesian doctrine called secular stagnation. There is absolutely no doubt we are in a period of economic stagnation, and that it is secular (i.e. long-term and not tied to the business cycle). The only problem in what they are doing is that they are looking for the causes of the stagnation in all the wrong places. They assume the causes lie in market failures of free-markets, rather than the government failures Gallup discovered in explaining the plot above. Nevertheless, Summer’s group of Keynesian economists at least acknowledge there is something very wrong with the advice given by Keynesian economists to governments around the world. If this stagnation continues under dirigiste policies, can there be any doubt that other dirigiste academics will begin to question their ideological faith?

What Takes Dirigisme’s Place?

What will be the new paradigm for ruling nations if dirigisme is finally rejected? We know what it will be in the short-term for the United States. With the election of Donald Trump and with his choices for cabinet appointments, there can be little doubt the U.S. will be ruled with neoliberal (conservative in common parlance) principles. However, this change may be ephemeral unless more Americans, particularly those of the Democratic persuasion, can be persuaded to convert to a new faith. To effect these conversions, Trump’s new administration will need to show dramatic improvements to the economy before the next mid-term elections. Otherwise, we can expect political attacks of increasing strength against his reforms.

However, the United States is not the only country caught in this unholy mess. Europe is also showing some signs of neoliberal stirrings, particularly in the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom, the recent Italian constitutional referendum, and in the developing campaign for the French presidency. Some European electorates appear to be on the verge of complete rebellion against the dirigisme represented by the European Union. If Trump’s policies can regenerate U.S. economic growth, this would encourage European neoliberals to seek the same kinds of reforms. If European neoliberals can find the policies to rejuvenate their economies, that would revitalize their American kindred. If neither of us can find the answers, a return to even more authoritarian government control of the economy would appear inevitable.

Views: 3,225