Alternative to the Keynesians: New Classical Economics

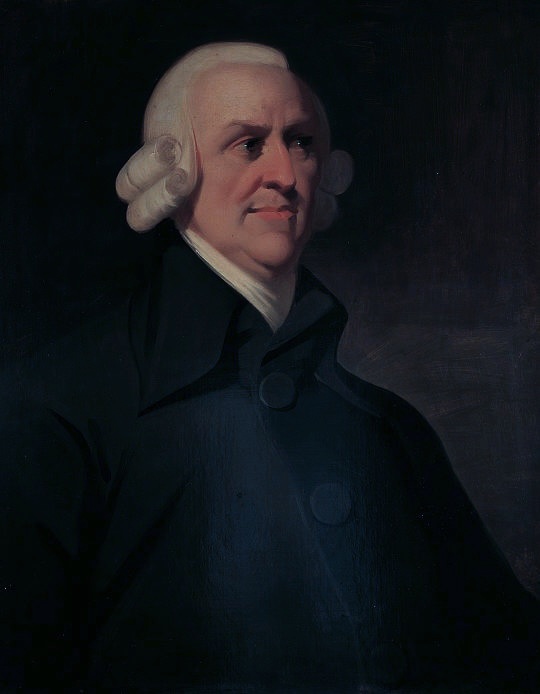

Adam Smith (1723-1790), founder of classical economics, which has flowered into New Classical Economics

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/By Unknown – http://www.nationalgalleries.org/object/PG 1472, Public Domain

At this time in history, the dominant school of economics is that version of Keynesian economics known as New Keynesian economics. As the New Keynesian school self-destructs all over the world with its bad predictions and prescriptions, we should look for more accurate alternatives. The corresponding school of neoclassical economics is known as the New Classical economics, sometimes also called the New Classical macroeconomics. Just as the New Keynesians added ideas of microeconomics in what they call the “new neoclassical synthesis”, the New Classical economists added ideas of macroeconomics derived from neoclassical economics. Examples of eminent New Classical Economists are Robert Lucas (recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 1995), Edward Prescott (co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in 2004), Finn Kydland (the other co-recipient of the 2004 Nobel Prize), Thomas Sargent (recipient of the Nobel Prize in 2011), John Muth, and Robert Barro.

In this introductory essay on the New Classical economics, I will start in the way the subject is introduced in textbooks. Starting with the neoclassical laws of economic, we will assume the economy is operating perfectly as a free-market economy with no perceptible intrusions by the government. Imperfections caused by such factors as imperfectly available knowledge and government taxes and regulations will be introduced in later posts. But first, let us look at a little of the pre-history to New Classical Economics.

Prehistory of New Classical Economics

The neoclassical laws of economics began with the law of supply and demand, discovered by the Scottish economist Adam Smith and explained by him in his classical work, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. The remaining classical laws are Say’s law of markets, and Ricardo’s law of comparative advantage. All of the classical economists believed in some form of an input theory of economic value. That is, the economic value of a good or service is determined by the values of the inputs (raw materials, labor, intermediate goods) used to make the good or service,

In the 1870s The Austrian economist Carl Menger, the Frenchman Leon Walras, and the Englishman William Stanley Jevons launched the neoclassical revolution. They modified classical economics by demonstrating the economic value of a good is determined by its utility to its buyers. They also explained with the law of

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons/mises.org

marginal utility what happens to the economic value of a good when its market becomes more saturated, or its cost of production and availability change. No input theory of value could explain all these phenomena. When joined with the law of supply and demand, marginal utility helps give a more accurate explanation of the operation of Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand. As explained in Economic System States, Feedback Loops, and Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand, the “invisible hand” is a metaphor for a free-market’s mechanisms for balancing the demand for goods and services with their supply.

Neoclassical economics, formed with the fusion of the law of marginal utility to the classical laws, dominated Western economic thought from the 1870s to the Great Depression in the 1930s. Starting with the Great Depression, the ideas of the British economist John Maynard Keynes, termed Keynesian economics, supplanted neoclassical economics substantially for two reasons: (1) it offered hope in the middle of a depression for a quick recovery while neoclassical economics was saying everyone had to wait for the economy to heal itself; and (2) it gave intellectual elites an excuse to begin centralizing economic power in the state. From that time to this, various forms of Keynesianism have mostly dominated economic thought and power.

During the 1940s and 1950s, the original Keynesianism morphed into neo-Keynsian economics. In this form, Keynesians had added ideas about microeconomics to their original macroeconomics in what they called their neoclassical synthesis. In particular, with the creation of the Phillip’s curve, they gave an explanation for inflation and deflation.

Neo-Keynesians Hit a Speed Bump, and New Classical Economics Arises, But Is Eclipsed By the New Keynesians

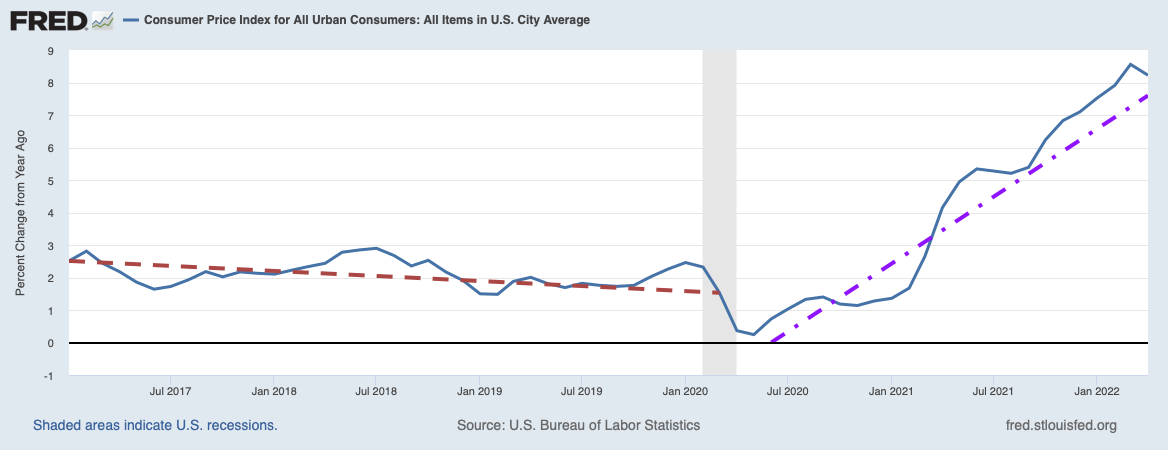

However, the 1970s laid a trap for the neo-Keynesians they could not possibly avoid. When the U.S. and other countries were hit by the oil supply shock of 1973-1974, economies depending on oil imports went into recession. The neo-Keynesians, in charge of the Federal Reserve (chaired by Arthur F. Burns) and believing in the Phillips Curve, set very low interest rates to exchange inflation for less unemployment. In fact the Fed had also set low interest rates in the previous decade to encourage growing employment, and had experienced growing inflation rates then. In the 1970s, however, the inflation ran away from them. The inflation rate as measured by the Consumer Price Index is shown below for the years 1955 to present. The entire period from 1965 through 1982 is known in monetary history as the Great Inflation. At its height, inflation reached 14.6% in March and April 1980.

Image Credit: St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank/FRED

But inflation was not the only economic effect of note in the latter half of the 1970s. As Milton Friedman correctly predicted, the inflation required by the Phillips curve to lower unemployment would continuously increase. As workers became used to a particular level of inflation, they would demand, and employers would deliver, an extra increase in their wages to account for inflation. In addition, the inflation delivered by the Fed’s monetary policy did nothing to better “real”, objective maladies such as the 1973 oil supply shock. Instead, the inflation worsened most economic agents’ capability to make demands by lessening the actual value of the money they had saved. (Economic agents are individuals and groups of individuals, such as companies, who buy and sell goods.) In fact, the inflation caused negative real interest rates for all savers! Eventually, as most people fell behind in the value of their assets, economic stagnation took hold with the recession of 1973-1975.

The neo-Keynesian school lost credibility due to this debacle, giving an opportunity for the New Classical Economics to rise. The origins of the school probably began with efforts by Robert Lucas and Leonard Rapping to provide a foundation for a Keynesian description of the labor market in neoclassical microeconomics. They were part of a small army of Keynesian scholars attempting to further the neoclassical synthesis by explaining consumption, investment, and other pieces of the neo-Keynesian model through microeconomics. They were part of a program for establishing the “microfoundations of macroeconomics”. In this establishment of microfoundations, economists generally assumed, given the expectations economic agents had of the economy, that those agents would make decisions to optimize their economic outcomes (incomes, profits, elimination of debt, etc.). Then, to some degree of approximation prices and wages would adjust to change the incentives for individuals to buy, invest, or to take jobs.

However, inconsistencies arose between some of these microfoundations and Keynesian theory on aggregates that caused some economists to separate from the neo-Keynesians into a distinct community of New Classical economics. Instead of using Keynesian aggregate theory to inspire microeconomics, with individual microeconomic decisions adjusting to the macroeconomic environment, the New Classical economists started with the neoclassical laws of economics and with assumptions about average human behavior to derive a macroeconomic theory, As a response to New Classical criticisms, New Keynesian economics developed from the late 1970s to the present. Under the impetus of the Great Recession of 2007-2009, the New Keynesians became dominant in academia and in power all over the world, but especially in the United States after the election of Barack Obama to President. Given the big economic mess the New Keynesians are making all over the world, we may again see a turn back toward the New Classical economics. (See Echoes of the Great Depression: America, Europe, and Japan, Echoes of the Great Depression: Europe, Echoes of the Great Depression: Japan, France in Distress, Quantitative Easing and Its Effects, Why Have ZIRP and QE Failed?, Economic Damage Created by the Fed, The Insanity of Negative Interest Rates, BOJ Also Losing Credibility And Its QE War, and The Bad Examples of the ECB and BOJ.)

Rational Expectations, Market Clearing, and “Real Business Cycles”

Beginning with my next post, I will begin the discussion about the main ideas animating New Classical Economics, starting with the ideas of rational expectations, market clearing, and real business cycles.

Views: 2,764