Information Sources For Our Hive Mind

The classic, arduous. time-consuming, and expensive way to access information!

A photo of a part of my library

A few days ago, I asked the question “How Can So Many See Such Different Realities?” in a post with the same title. A part of the answer comes from the observation that most of us think we know a lot more than we actually do. From long-term observation of my fellow human beings (I am currently 70 years old), I am firmly convinced this is a true statement even for the most erudite of us. It has certainly been true for me for more times than I would like to admit! In fact, it is almost certainly a condition that is impossible to avoid. In this post I would like to offer some suggestions on how to ameliorate the situation.

The Knowledge Illusion, Or “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

The immortal words in the quotation above are most usually attributed to the American author Mark Twain. However, if you do a Google search on the quotation, you can find that it was probably from some fellow called Josh Billings, aka Henry Wheeler Shaw (1818-1885). In a way it is rather satisfying the quote

Wikimedia Commons / TCS 1.2486, Harvard Theatre Collection, Harvard University

illustrates part of the reason why we all have so many different views of reality in two different ways.

I am indebted to a fascinating book, The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone by Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach [IP1] for much of the formulation of the problem I use here. They begin with the highly unoriginal observation that the knowledge of almost all human beings about their world is usually extremely superficial and limited. Because the world around is so complicated and we are focused on interacting with our environment usefully and fruitfully, we tend to abstract from available information just the bits we need to solve whatever our current problems are, whether practical or scholarly.

Sloan and Fernbach explain that the human mind is not designed to hold vast amounts of information like a computer. Instead, it is a flexible problem solver that tends to extract the information most useful “to guide decisions in new situations.” We almost always store very little detailed knowledge of the world in our own heads. As a result our total knowledge resides in a sense in a “collective mind” that includes the minds of many other human beings, both living and dead. Sloan and Fernbach make an analogy of the human intellectual community with a beehive, and they refer to the collective mind as the “beehive mind”. If we have actual need for the nitty-gritty details of any issue and they do not belong to our own field or fields of expertise, we can access those details in the beehive mind by reading books, watching a video, listening to or watching a newscast, or searching the internet.

We can not be at all surprised given these human propensities that so many different versions of reality have been constructed by so many people. We are all interested in somewhat different aspects of reality, and we abstract different aspects of it according to our different needs and interests. The situation is very much like the famous Indian fable of six blind men examining an elephant.

Then when someone’s view of reality conflicts with that of another, they often denigrate the conflicting view and deny that it could be abstracted from reality at all. There is a very real possibility they are quite correct to decry someone’s conflicting ideology, but there is a very real possibility they are wrong as well. The problem is one of interpretation of what we see and experience, as we try to fit our own patterns of connections with the observed facts. These differing ways of interpreting reality are our clashing ideologies, motivating our social and political wars.

Concerning our political wars, Sloan and Fernbach write in the introduction to their book,

This book is being written at a time of immense polarization on the American political scene. Liberals and conservatives find each other’s views repugnant, and as a result, Democrats and Republicans cannot find common ground or compromise. The U.S. Congress is unable to pass even benign legislation; the Senate is preventing the administration from making important judicial and administrative appointments merely because the appointments are coming from the other side.

One reason for this gridlock is that both politicians and voters don’t realize how little they understand. Whenever an issue is important enough for public debate, it is also complicated enough to be difficult to understand. Reading a newspaper article or two just isn’t enough. Social issues have complex causes and unpredictable consequences. It takes a lot of expertise to really understand the implications of a position, and even expertise may not be enough. Conflicts between, say, police and minorities cannot be reduced to simple fear or racism or even to both. Along with fear and racism, conflicts arise because of individual experiences and expectations, because of the dynamics of a specific situation, because of misguided training and misunderstandings. Complexity abounds. If everybody understood this, our society would likely be less polarized.

Yet, because we all want to be able to control our own lives, we can not allow technocrats, the experts, to have total control of us, which is what the favorite progressive mode of governing would be. This is especially true because history has taught us technocrats often have no clearer vision of reality than the rest of us. Witness the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the economic messes of communist China, Cuba, Venezuela, and of the early socialism of India. Or for that matter, the messes dirigistes in the West have made of their economies in recent decades.

If we are to remain a free people, we have an urgent need to be able to access our collective hive mind more efficiently, with less time and effort. To know the best political solutions to public problems — which might well be to allow people to solve their own problems and to keep government out of it — we need to have quick access to those nitty-gritty details. Luckily, we have a much more efficient method to access the hive mind than to visit the public library; we have the internet.

Sources From The Internet

Unfortunately, we have the same big problem in researching the internet as we have in researching at a library. The problem is one of finding reliable sources. There is an awful lot of intellectual junk on the internet, just as there is huge amount of junk to be found in many books. How do we separate the wheat from the chaff? The answer from empirical epistemology is to demand the maximum consistency possible between ideological depictions of the world with observations and data. This is the method that has made mathematics and the physical and biological sciences so successful.

That having been said, I have found a number of websites that have been particularly useful and reliable. Making you aware of them is my primary objective in this post. First there are websites at which you can find all sides of a particular argument. This does not necessarily mean the website is neutral in the argument, merely that they can be relied on to present all sides of a controversy. These are useful for framing the scope of the ideological disagreement for any particular issue. I will list links to these websites below, together with some notes on how they are useful.

- The Wall Street Journal: This is probably the best newspaper in the United States, which covers what is happening in economies all over the world together with coverage of political, social, and scientific developments of note. The WSJ has a generally neoliberal bias. Unfortunately, access requires a paid subscription.

- RealClearPolitics: The biggest contribution of this site is a collection of links to posts from many different websites expressing all sides of a political argument.

- RealClearMarkets: Very similar to RealClearPolitics, RealClearMarkets lists links from many websites covering all sides of economic controversies.

Next I must mention some websites from which you can find trustworthy economic data.

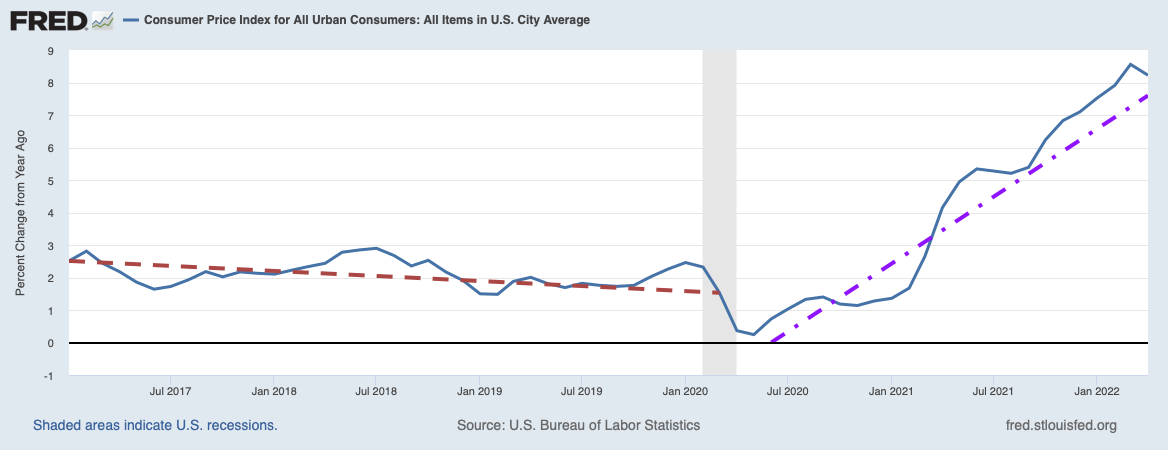

- The Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED): Maintained by the Federal Reserve District Bank of St. Louis, FRED holds a vast array of data on U.S. economic variables as time series. A tutorial on how to download data and to produce graphs of FRED data can be found here.

- The World Bank: The World Bank provides a publicly accessible databank for a large number of countries. Data on various measures of GDP and GDP growth are available. Also, the data available includes some interesting non-economic data as well, such as the GINI index for various countries, and education, health, and population statistics.

- The Heritage Foundation / Wall Street Journal Index of Economic Freedom: These indices and its constituent components for various countries gives an in-depth view of how much governments interfere with and control their economies.

- The European Union Open Data Portal: Everything you would want to know about the European Union!

Of more sociological interest is the United Nation’s Human Development Index (HDI), published annually at:

- The United Nations Human Development Reports: Just be careful about dirigiste, multiculturalist propaganda!

The following five sources provide a wealth of information on how the federal government spends and has spent our money.

- Historical Tables of the U.S. Government Budget: Published by the U.S. Government Publishing Office.

- The Congressional Budget Office (CBO): Congressional analysis of proposed spending.

- The White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB): Analyzes what the President wants to spend.

- The Heritage Foundation on the Federal Budget and Spending: Some independent analysis from the Right.

- The National Priorities Project: Some independent analysis from the Left.

Information on how the U.S. government regulates our lives and economy.

- Federal Laws and Regulations from USA.gov: Straight from the horse’s mouth!

- Regulations.gov: A government portal that allows you to review and comment on proposed U.S. government regulations.

- The Heritage House Foundation on U.S.Government Regulation: Some independent analysis from the Right.

- Environmental Protection Agency Regulations: Straight from the EPA!

The following two online encyclopedias are indispensable!

- Wikipedia.com: How could I live without it?

- Encyclopædia Britannica: A gold standard.

The next time you become interested in a public issue, do a little research. The more detail on the issue you glean from our collective hive mind, the better off you will be in forming a judgement.

Views: 2,610